By Ron Chepesiuk for Gangsters Inc.

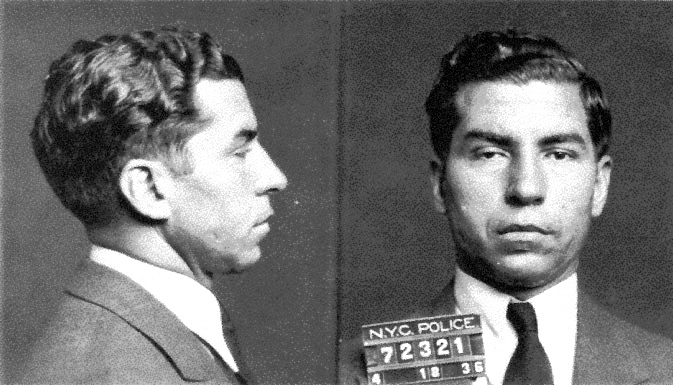

In 1935, Charles Lucky Luciano was perched pretty on top of the criminal world. He was the godfather of the powerful Genovese crime family, headed the Commission that oversaw all mafia activities in the U.S. and had taken out fellow mobster, the unpredictable psychopath Dutch Schultz, who had threatened the stability of the mafia world.

Luciano felt untouchable, but his notoriety had made him a marked man for an ambitious New York prosecutor named Thomas Dewey, who was determined to take him down. At the center of Dewey’s Luciano’s investigation, acting as his right hand person, was an unlikely hero: a 36-year old black woman lawyer named Eunice Hunton Carter. She had studied Luciano’s organization and was methodically and brilliantly putting together a case against the godfather that would make history by leading to the take down of, arguably the most powerful mobster in U.S history.

Eunice Carter was born on July 16, 1899, in Atlanta, Georgia, at a time when racial and gender inequalities cast long shadows over opportunities for African Americans. Her parents, William Alphaeus Hunton Sr. and Addie Waites Hunton, were prominent educators and activists who instilled in Eunice a deep sense of social justice and a passion for education.

After completing her primary education in Atlanta, Eunice moved to New York City to attend Smith College, where she graduated with honors in 1921. She was only the second woman in the history of Smith College to receive a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in four years.

After a brief career as a social worker, Carter, driven by her fervor for justice, went on to attend Fordham Law School, where she became the first black woman to graduate in 1932. Her academic achievements were a testament to her intellect and determination to break barriers in a profession dominated by white men.

Later, Carter would say, “A country or community which fails to allow its women to choose and develop their individual beings in an atmosphere of freedom thrusts away from itself a large part of the human resources which can give it strength and vitality.”

Upon earning her law degree, Eunice Carter faced the harsh realities of racial and gender discrimination that permeated the legal profession of the time. Undeterred, she joined the law firm of her brother-in-law, Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, becoming the only black woman attorney in New York City during that era.

In 1935, Eunice took a momentous step in her career by accepting a position as Assistant District Attorney in the New York County District Attorney’s office. This was a significant milestone for both her and the African-American community, as it was nearly unheard of for a black woman to hold such a position of authority at the time.

Eunice Carter’s efforts did not go unnoticed. She caught the attention of New York District Attorney Thomas Dewey (left), a rising star in American law enforcement known for his uncompromising stance against organized crime. Indeed, Dewey was relentless in his effort to curb the power of the American mafia and of organized crime in general.

Dewey would later serve as 47th governor of New York from 1943 to 1954 and was the Republican Party’s nominee for president of the United States in 1944 and 1948, where he lost in a major upset to Harry Truman. Carter would rise to importance in the Republican Party, playing a role in Thomas Dewey’s presidential bids in 1944 and 1948.

Interestingly Dewey had almost arrested Dutch Schultz, but ironically Lucky Luciano had Schultz murdered after he threatened to assassinate Dewey.

Dewey appointed Carter to a team called “Twenty against the Underworld”. She was the only black and only female lawyer on the team.

Soon Dewey recognized Carter’s exceptional legal acumen and dedication to justice, and he appointed her as the chief prosecutor in the case against Luciano. It was a remarkable rise for Carter, but her upward career climb was not easy. She faced formidable odds but would not let the blatant racism of the times thwart her career ambitions.

Yet, as historian Stephen Carter wrote in the New York Times, about the racism Carter endured, she “could never quite escape its noxious hold on American society, whether it was being paid far less than her white male peers on Dewey’s staff or being passed over, in favor of a rival, for a prestigious judicial appointment.”

Together, Carter and Dewey formed a formidable team. Dewey provided the resources and support needed to mount a comprehensive investigation, while Carter brought her unparalleled expertise in building a case with precision and tenacity.

Eunice Carter was a memorable figure in the Halls of Justice. Her dignified posture exuded confidence. She had expressive, intelligent eyes that reflected her sharp mind. Her refined features were often framed by meticulously groomed hair, a testament to her keen attention to detail. She carried herself with a poised and composed demeanor, which underscored her unwavering commitment to her work.

Carter’s brought a combination of shrewd legal strategy and tireless dedication to the Luciano case. She understood that, to dismantle Luciano’s criminal network, it was essential to target the linchpin of his operation—his formidable prostitution ring known as “The Combination”. Her brilliance lay in her ability to see the bigger picture, identifying the interconnectedness of various criminal activities and building a comprehensive case against Luciano.

Carter understood that to weaken Luciano’s criminal organization, she needed to focus on a specific aspect of his illegal activities. In New York City, she had been a prosecutor in what was then called “women’s court” — that is, a court for the prosecution of women, especially prostitutes. She honed in on Luciano’s prostitution ring and began building a case around it.

On May 13, 1936, the case against Charles “Lucky” Luciano went to trial. Prosecutor Thomas Dewey went on the attack, exposing Luciano as a liar and connecting him to his prostitution ring.” Dewey had a star witness, Florence “Cokey Flo” Brown, a drug addict, former madam and prostitute, and 27 other ex-working girls that helped Dewey present a formidable case. Brown testified that an acquaintance had told her about a madam who was beaten up by Tommy “the Bull” Pennochio on Luciano’s orders.

Then Luciano made a crucial mistake. He took the stand in an effort to rebut the witnesses’ statements. He challenged the 27 prostitutes who testified against him, claiming they were liars.

Then it was Dewey’s turn to cross examine Luciano, and disaster struck the godfather. It appeared that the women arrested for prostitution, who were from all over New York City, were represented by the same lawyers and bail bondsmen and that those lawyers and bondsmen had a relationship with Luciano. Dewey questioned lucky about the lavish lifestyle he enjoyed on a reported income of just $22,500 per year. Dewey used phone records to connect Luciano to notorious gangsters, including the notorious Louis “Lepke” Buchalter.

The jury was convinced. Thanks to Eunice Carter’s meticulous preparation and unwavering determination, the prosecution secured a conviction. Luciano was found guilty on charges of compulsory prostitution and was sentenced to 30 to 50 years in prison.

Eunice Carter’s role in this landmark case marked a significant victory not only for the fight against organized crime but also for breaking down racial and gender barriers within the legal profession. Her pioneering efforts paved the way for future generations of African-American lawyers and prosecutors, demonstrating that excellence and determination could triumph over prejudice and discrimination.

Carter continued working with Dewey and the District Attorney’s Office until 1945, when she entered private practice. By that time, Carter’s reputation had caught the attention of prominent legal figures and institutions. She received invitations to speak at conferences, seminars, and legal symposiums across the country, where she shared her insights on criminal justice, organized crime, and the importance of upholding the rule of law. These engagements allowed her to influence and inspire a new generation of legal minds.

Beyond her professional accomplishments, Eunice Carter continued to be an advocate for civil rights and social justice causes. Her commitment to equality and fairness extended beyond the courtroom, and she remained actively involved in community initiatives and organizations dedicated to advancing the rights of marginalized communities. After her retirement, Eunice Carter remained active with numerous organizations, including the United Nations, the National Council of Negro Women and the YWCA.

In addition to her public recognition, Carter’s expertise was sought after by various law enforcement agencies and organizations. She was approached to provide counsel on complex legal matters, particularly those related to organized crime and racketeering. Her invaluable insights and strategic thinking became assets in the ongoing battle against criminal enterprises.

Eunice Carter died in 1970, but her contributions to the law continue to inspire and shape the trajectory of legal professionals to this day.

Ron Chepesiuk is a journalist, screenwriter and author of Black Caesar: The Rise and Disappearance of Frank Matthews, Kingpin.

Leave a Reply