By Thom L. Jones for Gangsters Inc.

According to Giuseppe Montalbano, a deputy in the Regional Parliament, “Sicilians are by nature delinquents, all mafiosi or tending to mafiosi.” To him, “the mafia constituted an occult middle class with its fingers in every social stratum, imposing on the aristocracy while intimidating the peasant.” *

Late, thirty minutes before midnight, on August 22, 1956, Nino Cottone was dead.

History reminds us to tell the truth, then at times, leads us down dark alleys infested with deceit and fabrication. Sorting out the fact from the fiction is an endless puzzle that faces investigation into the Mafia history of Sicily. The brutal killing of a man outside his home in a small town on the outskirts of Palermo was a last act in a drama over oranges and lemons and mandarins.

Like so many of his peers, his end was violent, planned, and engineered for a purpose.

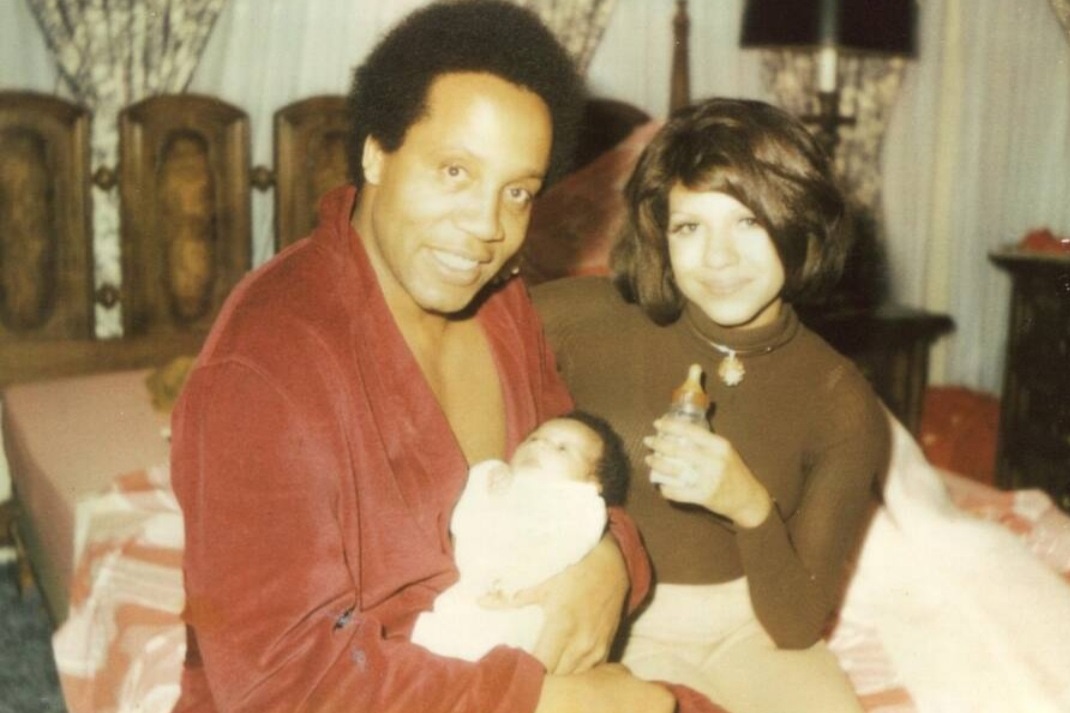

In the endless, internecine wars within the Mafia, which have prevailed as long as its existence, the murder of Antonino Cottone (right) and the killings of others linked into the dispute over control of Palermo’s fruits and vegetable market, was an episode in a never-ending story as violent men used violent means to establish control over their territories.

Power, money and prestige, the three pillars that have always supported the structure of the Mafia, will drive the narrative in the life and death of a less-well know figure in Sicily’s criminal underworld. Although he was only fifty-two at his death, Cottone had packed a lot into his lifetime.

Born in Villabate in 1904, he was destined for a Mafia life, almost by default. The Cottones had been part of the criminal substructure in the town for generations. One by this name was the boss in the 1890s, according to the famous Sangiorgi Report.**

Another family member, Andrea, would be a victim over a hundred years later in 2002, as he played a losing hand in yet another mob struggle for power.

Nino was one of thousands rounded up in the great anti-Mafia campaign of 1924-1929 under the direction of Cesare Mori, which was supposed to destroy the mob and almost did, although he survived to live another day.

One of his family, perhaps Antonino, or his father, Vincenzo, was confirmed as the boss in 1937 by Melchiorre Allegra, a Mafioso from Castelvetrano, arrested in a major attack on the organization carried out by The Inspectorate General. Another Andrea, was the family’s consigliere or counsellor in this period in the late 1930s.***

Villabate has a long history of Mafia connections, even though it had only about 8,000 citizens in the 1950s. A Mafioso from the town, Giuseppe Fontana, was almost certainly involved in the murder of one of Sicily’s leading citizens, Emanuele Notarbartolo, a former head of The Bank of Sicily. Giuseppe Profaci, a clan member and family friend of Cottone, left the town in the early 1920s, emigrated to New York and became head of one of the city’s five Mafia families. The town may also have been the home to the first Mafia family to produce a pentito, a government informant, in the 1870s.

Following the end of World War Two, the military government appointed Nino the mayor of Villabate. He was on the surface, a butcher, running a retail shop in a town with seven others, and yet somehow, he was eminently more successful. He owned land and properties. A man of substance in a place filled with peasants, who would bow to him and touch his hand as he walked down the street, calling him u patre nostra, “our heavenly father.” Their benefactor, who ruled their community by offering protection from threats that he himself created.

The term “father” is one a Mafioso was fond of in Sicily, and adopted by Michele Navarra, boss of Corleone, Genco Russo of Mussomeli and the fearsome Sacco Vanni of Camporeale to name a few.

A famous Sicilian author, Leonardo Sciascia, once wrote, “The silence of the honest and the dishonest will always protect the Mafioso.”

His contacts within the Sicilian Mafia extended to the man who was allegedly the big boss of all bosses – Calogero Vizzini – whose domain was in central Sicily in Villalba, in the province of Caltanissetta. It was claimed whenever he travelled to Palermo, he would always stop on route, to meet and greet Cottone.

Rumors circulated Nino was working with cattle rustlers (abigeato was a major activity by the mob in rural Sicily) connected to a young and very dangerous Mafioso from the town of Corleone. His name was Luciano Leggio, making his own way in the honored society.

This was how butchers could avoid the commercial costs of legitimate supply chains and undercut their competitors. Cottone allegedly took part in illegal activities, including cigarette smuggling, trafficking immigrants, and extortion. A well-rounded criminal, who also had excellent political connections at both local and state level.

An internet site, highly regarded by Mafia historians, claims that Antonino Cottone moved to America in the 1930s. It claims:

“COTTONE-ANTONINO 1904 Villabate, Sicily /USA?

Alias: – Nino

Relations: – Profaci brothers [?].

The Cottone family were related to the Profacis in Villabate, and both were active in the local Mafia cosca. Nino Cottone was probably inducted in Sicily, and came to America in the 1930s. He worked for Joseph Profaci, in his Olive Oil business, and was accepted into the Family. An illegal immigrant, the authorities caught up with him and he was deported back to Sicily (date unknown). Became active again in the local cosca, he rose to head it by the 1950s. He became involved in a conflict, and was killed in 1956. His sons were also members of the Villabate cosca.”****

Various Italian web sites and legal documents such as parliamentary hearings and investigations into the Mafia also mention this, although it’s difficult to pin down exact details about Cottone’s movements during this period.

There are reports that when he returned to Sicily, he set up a heroin ring and exported the product to Profaci hidden inside hollowed-out oranges. Again, trying to confirm this is hard. Of the five Mafia clans in New York, Profaci’s was apparently the least involved in drug trafficking as a revenue creation.

Historical records show Cottone was initiated into Freemasonry through the Lux Masonic Lodge of Palermo in 1944 and stayed a member until his death. A mob boss in Sicily is always a Mason. Through this connection, they mix with other men of power – politicians, business people, high church – the institutions who control the destinies of many.

His business and criminal activities began long before that date; when he moved to America and returned is still unknown. Investigators realized tracking his criminal progress, that he was creating links with public officials, administrators and financial institutions, while contesting rival gangs fighting for a share of the spoils. Above all, he would network his political opportunities.

Both the local mafia and those overseas because of his kinship with the gangsters of New York feared and revered him an Italian parliamentary report claims. He was allegedly a friend and working associate of Charlie Luciano, the infamous gangster deported from America in 1946 back to Sicily, his birthplace.

Nino Cottone was definitely in Villabate when a war broke out between two families.

To the south of Palermo City, under the cliffs of Mount Grifone, communes and settlements here have felt the odor of the Mafia for generations. Three in particular, feature often in records of violence and sudden death: Ciaculli, Croceverde-Giardina, and Villabate.

An area famous for its citrus orchards, for generations, it has been a battleground for warring factions and inter-family disputes. Two different groups with the same name, Greco, although only distantly related, began killing each other in 1939. The name is possibly the only common denominator connecting the families.

A Salvatore Greco is listed in the Sangiorgi report as the capo mafia of Ciaculli. The family controlling the borgata or village from the nineteenth century onwards through management of the guardiani (rural watchmen) and irrigation systems, abigeato (cattle-rustling) and smuggling and racketeering involved in the production and trade of citrus fruits for local, national and transatlantic markets.

Another Salvatore (right), called “The Senator” later in life, is the son of boss Giuseppe, known as Piddu who headed the group in Croceverde, and marries Maria, a daughter of Cottone, a common method used by Mafia groups to keep their families in The Family.

Salvatore’s brother, Michele, was well known in the Sicilian Mafia from 1970s-1990s, leading their governing body, The Cupola.

Part of the endless puzzle mentioned earlier is trying to make sense of the names of the leading figures who move through mob stories like endless conundrums designed to frustrate and confuse us. In Sicily, they often name male children after fathers and grandfathers, allowing for multiple repetitions within the same family groups.

In 1947, Joe Profaci surfaced again, reportedly spending a month in Sicily, likely in October, and supposedly used his influence in resolving the conflict between the two groups who agreed to settle their differences.

When all was done and dusted, they shared the spoils of war between them. The struggle appeared to be a family-type vendetta, but was more likely triggered to gain control of citrus orchards, futures trading, trucking contracts and wholesale markets in eastern Palermo.

In the Mafia, money trumps everything, every time. Except power.

The ‘fruit of death’ is an idiom pointing to a situation in which dire consequences or outcomes result from a single event or decision. One wrong decision can lead to disaster. For Antonino Cottone, that will be a decision which the city council of Palermo will make in the early 1950s.

In January, 1955, they moved the city’s mercato outofrutticolo, the fruit and vegetable market, from its site on Via Guglielmo in Zisa to a new location off Via Duca Della Verdura in Aquasanta, near the port of Palermo.

Within months, the killings began.

The Grecos of Ciaculli and Croceverde and the Villabate Mafia had long claimed rights over the produce market and, with the move to Aquasanta, the power base shifted. The local Mafia cosca believed their new neighbor was there’s for the taking and started tilting the scales accordingly.

Two gunmen shot dead Gaetano Galatolo, the Mafia boss of Aquasanta, in May 1955, while he was carrying out business in the newly opened complex, which may have been the first act of violence in the war over control of the market.

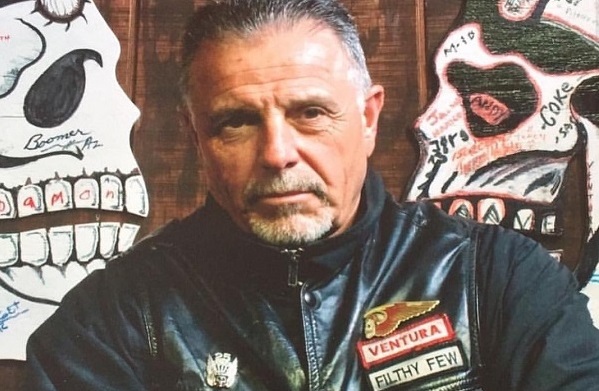

One of his killers was a man he knew well, Michele Cavataio (right), one of his own gang. An ex-cab driver with a psychopathic habit of killing all his problems, he would turn the Mafia on its ear in 1962, starting what historians call “The First Mafia War,” and then seven years later, when he became himself a victim of mob violence.

Mafia wars have been a part of their culture since day one. The early 1960s confrontation was simply a continuation of the struggle to gain absolute power.

Cavataio may have been using the dispute over the market as a way of fighting his way to the top of the tree, or he may have been in league with the opposition. We will never know, although either presumption is logical in the twisted, dark maze of Mafia mentality.

Galatolo, his brothers and kin, were prominent members of the Mafia in the Palermo area with a long history of criminal malfeasance, wielding power through their control of Palermo’s port and docks. Generations of their family have continued to carry on the business of crime within the biggest city in Sicily, scattering bodies in their wake. Corinthian farmers sowing seeds of death.

In June, 1956, police were called to a body found on the Corso Vittoria Emanuele in Villabate. It sprawled in the dirt in front of a house at number 854, directly opposite the home of Cottone. Identified as Luigi Paparopoli, age 44, he was the brother-in-law of Giuseppe Greco.

They found a pistol in his right hand, and it seemed he had committed suicide, apparently shooting himself twice in the head, right temple. Except there were no powder burns. No smoke soiling or tattooing, always found when a gun is held close to the skull. Paparopoli, a produce merchant, was closely involved with the Grecos and Cottone in the fruit and vegetable market control.

In March, someone shot and killed Francesco Greco at his home in Torrelunga, a few kilometers north of Villabate. He was another merchant connected to the Ciaculi/Villabate mob.

The newspapers reported that the Aquasanta Mafia, led by Cavataio, and their allies, the Grecos, finally resolved the dispute after murdering over eighty men over almost two years.. Nino Cottone was one of them.

His time came at the end of a long, hot day in August.

He owned two properties on via Corso Vittorio Emanuele, one in the town and the other, further south, more into the countryside. This one had vast citrus fruit groves as part of its estate. Cottone had purchased it for 47 million lire, about US$ 25,000, a significant amount of money in those days for a retail butcher. Over $300,000 in today’s currency. The annual average income in 1956 Sicily was equivalent to US$128.

About 11.15 on this evening, he leaves his house in town and drives his grey Fiat station wagon to the other property. One of its boundaries butted into a garage belonging to Giuseppe Pitarisi. It was closed, but not unoccupied. Sometime that evening, men had broken into the building through the rear door, and position themselves along the tray of a lorry parked against the inside wall which faced the Cottone property. Along this wall were multiple ventilation slots.

An article in Time Magazine tells us:

“One night last week prosperous Nino Cottone, 52, returning home late, gently backed his little Fiat station wagon into the drive of his summer villa. He had just locked the car when he was bowled along the driveway by two streams of machine-gun bullets. As his family and friends poured out of their houses, Nino painfully lifted up his bullet-ridden body and stumbled to the threshold of his villa, where, leaning against the door, he died on his feet as a good Sicilian should.”

It was a lot more prosaic.

As Nino left his vehicle, turning to lock it, the men in the garage presented shotguns through the ventilation slots, letting loose a massive volley of gunfire. Investigators will find 36 empty cartridge cases scattered across the garage floor and one, fully loaded unfired, J6 buckshot shell that had slipped from a cartridge belt or a pocket.

Riddled with the shot, Cottone dies instantly. Neighbors alerted by the noise rush to the scene. One is Doctor Rafael Schillaci, but all he could do is confirm the victim was dead. The killers disappeared into the night, down roads or across fields. The murder has never been solved. A textbook Mafia hit by boias (killers) who knew their trade.

The following day, while driving a borrowed mule-drawn cart down a dusty lane in Resuttana, a village in the north-west of Palermo, someone shot dead Angelo, brother of Gaetano Galatolo.

If this is about scoring dibbing rights in the Palermo fruit and vegetable market, the circle is almost complete. There will be bodies falling and disappearing in the months ahead until Cavataio and the Grecos declare a truce and work out a timeshare of their extortion ambitions.

The evening Angelo dies, back in Villabate, shots are fired at Giovanni Di Perri, age 37, as he stands outside the family garage. Badly wounded, he survives, but kismet awaits him. On Christmas Day, 1981, he is one of three men killed in what becomes known as “The Bagheria Massacre.” He is then the current boss of Villabate Mafia and a victim in the great Mafia War of the 1980s.

In an endless session of stop, kill, reset, Mafia clans regenerate like salamanders in their epimorphic restoration.

Back in 1956, at the funeral of Nino Cottone, his brother had sworn revenge against the Di Perri family who he claims masterminded the murder of the man hundreds farewelled, including many politicians from local and state agencies. By government estimate, the Mafia controlled 500,000 plus votes on the island. The Don of Villabate had himself, had power over more than two thousand in his area. At election time, they ration their votes, generally to the Christian Democratic Party. In return, favours given were always favours received.

Following the Don’s murder, in mid-September, state police and carabinieri forces launch “Operation Rateni” swooping on the towns of San Giuseppe Jato, Sancipirello, Rocella and Villabate rounding up dozens of suspects.

It had little effect.

Two weeks later Girolamo Ingrassia, a key figure at the produce market and ally of Cottone, was at the bus stop on Piazza Figurella, in Villabate at 2.30 pm. People filled the area attending the market day. Two men approached him and shot him dead using a shotgun and pistol. Other men using sub-machine guns lay covering fire down, hitting a young girl leaving the bus.

The gunmen showed no concern for the safety of the crowd as they sprayed deadly bullets, injuring the woman and endangering over 200 people.. Investigators believed the killers, who were part of the Aquasanta Mafia clan, committed the crime with no concern for the safety of the crowd. However, as almost always, the authorities failed to bring anyone to justice for the crime.

It is almost seventy years since Antonino Cottone stepped out of his little gray Fiat and into his own special hallway of darkness.

“Far from being solely or above all the fruit of a bloody and uncontrolled instinct or of a marginal subculture, Mafia murder is mainly pre-meditated murder, it is inspired by strategic logic.”

These words from Chinnici and Santino tell us everything about the power over life and death men like Cottone dispensed and received. Judge Cesare Terranova, assassinated by Mafia hit-men in Palermo in 1979, claimed: “The myth of the Mafioso as a brave, generous man of honor must be dispelled…willing to go to any length to save himself from danger, to avoid the just rigor of the law, and the consequence of his roguery.”

As a magistrate who had studied them, prosecuted them and died at their hands, he knew how easy it was to spill Sicilian blood.

Footnote to this story. As recently as 2018, Palermo’s Anti-mafia Investigations Directorate (DIA) confiscated assets worth more than 150 million Euros from two brothers, who had for years controlled Mafia infiltration of the city’s largest fruit and vegetable market.

Angelo and Giuseppe Ingrassia both 61 years of age, were linked into Cosa Nostra, and using a front company, exercised hidden control over the sale of produce in the market on behalf of the Galatolo clan of Aquasanta, the DIA’s investigations found.

Although the music of the Mafia has transformed over the last thirty years, the melody stays the same.

* Giuseppe Montalbano (19 June 1895–29 October 1989) was an Italian politician, born in the province of Agrigento.

** Ermanno Sangiorgi was the police chief in Palermo whose investigation and subsequent reports revealed the existence of Mafia clans and their crimes in the eastern Palermo Province between 1898 and 1900. It was the first in-depth study of this criminal phenomena that had plagued Sicily for decades. Like all prophetic reports exposing the embarrassing truth about Italy, politics and organized crime, they filed it away in archives, and it remained unknown until discovered a hundred years later.

***Allegra, after his arrest, confessed to his position and details about the Mafia in a statement that ran to 26 pages on July 23, 1937 at the police headquarters in Alcamo, Trapani Province. The first time a made member of the organization had disclosed such details. However, the document was filed away and not published until 1962 by l’Ora, the Palermo daily newspaper. The Mafia kidnapped and murdered Mauro De Mauro, the journalist who disclosed the confession, in 1970. No one has ever found his remains..

****mafiamembershipcharts.blogspot.com January 16, 2016. Hosted by Bill Feathers.

Sources:

The-Mafia-and-Capitalism.-An-Emerging-Paradigm-Schneider-Schneider. 2011. Sociologia.

Marino, Giuseppe Carlo. Storia della Mafia. Newton Compton, 2008.

Allen, Edward J. Merchants of Menace. Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, Illinois, 1962.

Cawthorne, Nigel. The History of the Mob. Arcturus, London, 2012.

Sterling, Claire. Thieves World. Simon and Schuster, London, 1994.

Chinnici, Giorgio and Santino, Umberto. La Violenza programmata. Franco Angeli, Milano, 1991.

Time. September 3 1956.

Cambridge. Org. Hands over the city. The Mafia, L Óra and the sack of Palermo.

Session CXXI Wednesday October 10,1956. Parliamentary Report 3071, Sicilian Regional Assembly.

Commissione Parlamentare D’Inchiesta Sul Fenomeno Della Mafia in Sicilia (Legge 20 Dicembre 1962, N. 1720)

Palermo Today. May 20, 2021. Sandra Figlirolo. Murder of Andrea Cottone.

https//www.senato.it

Palermo Today. August 14, 2018.

La Stampa 25 August, 1956.

I’Ora 23 August, 1956.

Giornale di Sicilia 24 August, 1956.

Copyright © Thom L. Jones & Gangsters Inc.

Leave a Reply